The way crews onboard the International Space Station and future explorers on lunar and Martian outposts sustain themselves combines cutting-edge technology with age-old agricultural principles. This article delves into the evolution from fully processed meals to the cultivation of fresh plants in orbit. By examining key strategies, experiments and design philosophies, we reveal how the nexus of space farming and closed-loop systems promises to revolutionize off-Earth nutrition.

Preservation Methods for Space Food

Long before any seedling sprouted in microgravity modules, astronauts relied on intensive preservation techniques to ensure safe, nutritious meals. The most ubiquitous approach is freeze-dried food. By freezing ingredients at extremely low temperatures and then sublimating ice directly into vapor, freeze-drying removes moisture while retaining flavor and nutrients. Compared to thermal canning, this method reduces weight and minimizes the risk of spoilage over months or years.

Another common practice is thermostabilization through retort pouches. Foods are sealed in flexible, multi-layered packages and heated under pressure to deactivate pathogens. This technique yields meals that remain shelf-stable at ambient station temperatures, making them ideal for staples like stews, soups and sauces. While durable, thermostabilized items can compromise certain heat-sensitive vitamins, so menu planners strive to balance convenience with nutrient preservation.

Irradiation represents a supplemental barrier against microbial contaminants. By exposing packaged foods to controlled doses of gamma rays or electron beams, technicians in terrestrial labs reduce bacterial load without significant heat exposure. The result is extended shelf life and enhanced safety—a crucial factor when resupply opportunities are limited.

- Benefits of freeze-drying: reduced mass, minimal water content, easy rehydration

- Strengths of retort pouches: durable packaging, wide menu variety, consistent nutrient retention

- Role of irradiation: microbial control, extended storage timelines, compatibility with other methods

Crew members prepare these preserved items by adding hot or cold water, then stirring or shaking the contents. The simplicity of this process is vital in microgravity, where loose liquids and crumbs pose contamination risks for ventilation systems and equipment.

Growing Fresh Crops in Microgravity

With the goal of improving diet diversity and psychological well-being, space agencies have invested in research on hydroponics and aeroponic cultivation systems. Hydroponic modules suspend plant roots in nutrient-rich water, while aeroponic units mist roots with fine droplets, maximizing oxygen exposure. Both approaches eliminate soil and its associated mass, making them ideal for weight-constrained missions.

Successful experiments on the ISS, such as the Veggie and Advanced Plant Habitat facilities, have demonstrated the viability of leafy greens like lettuce, mizuna and mustard. Red romaine lettuce harvested in orbit exhibited nutrient levels comparable to Earth-grown specimens. These victories relied on precise control of light spectra, delivered by arrays of LEDs tuned to blue and red wavelengths—the bands most efficient for photosynthesis.

Key to microgravity cultivation is root zone management. Without gravity to orient plants, roots can become entangled or deprived of oxygen. Engineers incorporate porous wicks, spacers and small fans to maintain even nutrient distribution and air flow. Sensors monitor pH, electrical conductivity and humidity, feeding data to automated controllers that adjust irrigation cycles.

- Advantages: higher vitamin content, reduced reliance on resupply, improved morale

- Challenges: fluid management in microgravity, pathogen control, limited crop variety

- Solutions: specialized growth media, real-time sensor feedback, targeted LED lighting

Beyond lettuce, recent trials have yielded dwarf wheat, mustard greens and even tiny radishes. Each new species expands the menu and provides fresh sources of vitamins A, C and K, essential for long-duration missions.

Integrating Agriculture into Life Support Systems

Looking ahead, future habitats will leverage bio-regenerative life support that integrates plant cultivation with waste recycling. In such systems, plants absorb carbon dioxide exhaled by crew, release oxygen, and purify water through transpiration. Meanwhile, organic residues—inedible biomass and human waste—can be composted or processed into nutrient solutions, completing a closed loop.

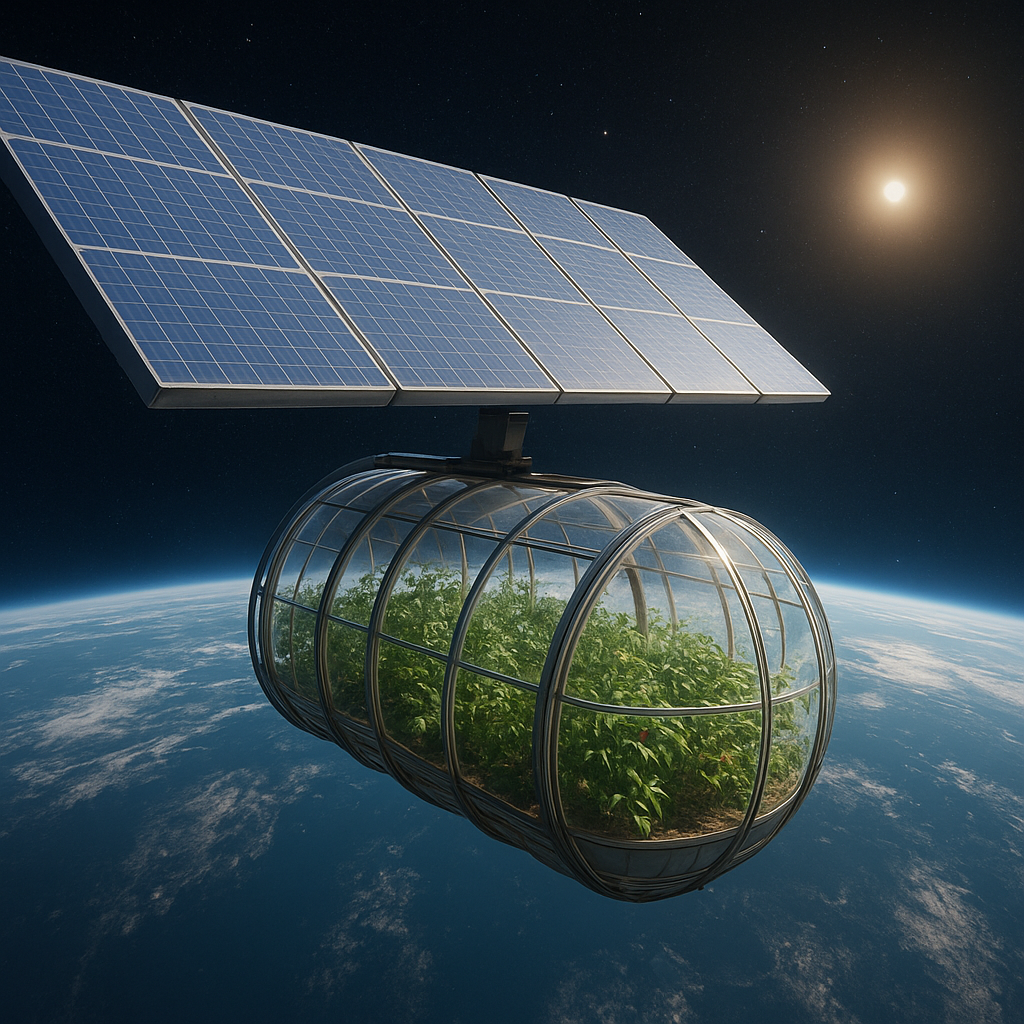

Designs for lunar or Martian greenhouses envision modular growth chambers shielded against radiation, with transparent domes or regolith walls providing insulation. Inside, multiple tiers of hydroponic racks optimize surface area, and LED panels supply up to 250 micromoles per square meter per second of photosynthetically active radiation.

Such systems demand careful nutrient cycling. Recirculating water streams must be sterilized to prevent algal growth, while mineral imbalances require periodic adjustment. Advanced control algorithms and machine learning may soon allow these habitats to self-regulate, minimizing astronaut intervention and conserving precious time.

- Closed-loop benefits: reduced resupply mass, sustainable resource utilization, resilient habitat ecosystems

- Technical hurdles: balancing gas exchange rates, nutrient recovery efficiency, system redundancy

- Future directions: AI-driven environment control, modular expansion, integration with 3D-printed infrastructure

Feeding Explorers on the Moon and Mars

As space agencies prioritize crewed missions to the lunar south pole and eventually Mars, menu planning must adapt to prolonged isolation and limited cargo windows. Early outposts will rely heavily on preserved foods, but incremental deployment of agriculture modules will enhance self-sufficiency. Initial lunar greenhouses may grow leafy vegetables within months of landing, leveraging solar exposure through orbiting mirrors or radiation-hardened windows.

Mars missions present unique challenges: reduced gravity, higher radiation and greater communication delays. Systems tested in analog habitats on Earth, such as Biosphere 2 and desert research stations, inform greenhouse designs for Martian conditions. Protective soil covers or regolith-based bricks shield crops from cosmic rays, while subterranean or inflatable structures maintain stable temperatures.

Long-term settlement envisions fully autonomous nutrient cycling networks that process inedible biomass into fertilizer, water and even building materials. Combining microbial bioreactors with plant growth paves the way for a self-reliant colony, where astronauts transition from consumers to true space farmers.

Ultimately, mastering off-Earth agriculture is not only about calories. It is about enhancing crew health, morale and sense of connection to a living ecosystem. Through ongoing research and innovation, the dream of fresh tomatoes grown on Mars or kale harvested on the Moon inches closer to reality.