As humanity sets its sights on long-duration missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond, establishing reliable systems for producing oxygen and edible biomass becomes critical. Harnessing the power of plants offers a dual solution: generating breathable air through photosynthesis and supplying fresh nutrition to crew members. This article explores the biology, engineering, and operational strategies for cultivating plants in space, enabling truly sustainable off-world outposts.

Photosynthesis in Microgravity Environments

Plants convert carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and biomass by capturing light energy. In space, the absence of gravity alters fluid distribution, root anchorage, and gas exchange. NASA’s Veggie and Advanced Plant Habitat experiments aboard the International Space Station (ISS) have demonstrated that, with the right environmental controls, higher plants can thrive even when microgravity affects sedimentation and convection.

Mechanics of Plant Growth

- Root Zone Management: Without gravity, roots require engineered substrates or wicks to direct water and nutrients. Hydrophilic anchoring mats and aeroponic misters ensure uniform moisture delivery.

- Gas Exchange Optimization: Boundary layers become thicker in microgravity, reducing CO₂ uptake. Fans or forced convection systems maintain a stable supply of carbon dioxide and remove oxygen buildup.

- Light Distribution: Uniform irradiance is crucial. Advanced LED lighting arrays with customizable spectra ensure plants receive the optimal wavelengths for chlorophyll absorption, adjusting red-to-blue ratios to accelerate growth.

Engineering Controlled Ecosystems

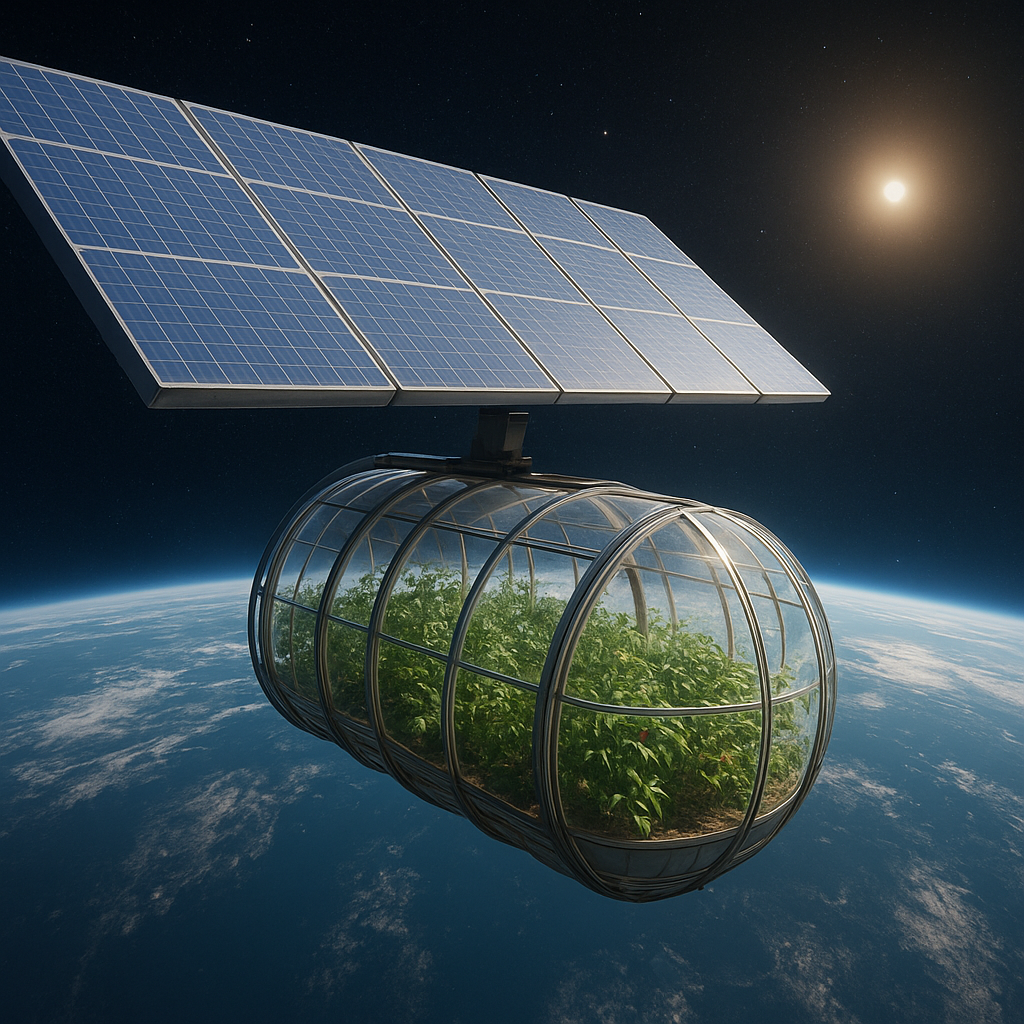

Spacefarers rely on closed or semi-closed life support systems that integrate biological and physicochemical processes. Known as bioregenerative life support, these ecosystems recycle waste streams—urine, fecal matter, and cabin air—into water, nutrients, and oxygen. Key components include plant growth modules, algal bioreactors, and abiotic processors.

Hydroponics and Aeroponics Systems

Water scarcity and mass limitations make soil-based agriculture impractical in orbit. Instead, soilless techniques prevail:

- Hydroponics: Nutrient-dense solutions circulate continuously through root zones. Sensors monitor pH and electrical conductivity, ensuring nutrient availability without stagnation.

- Aeroponics: Roots hang in mist chambers, receiving fine droplets of water enriched with macro- and micronutrients. Aeroponics often yields faster growth cycles and reduced water use by up to 90% compared to conventional farming.

Advanced cultivation racks incorporate modular trays, automated dosing pumps, and waste recirculation loops. Researchers optimize nutrient recipes that balance nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and trace elements while preventing salt accumulation. This level of control allows for predictable yield cycles and minimal crew intervention.

Integrating Bioregenerative Life Support

Beyond plant modules, comprehensive systems must handle purification, energy input, and automation. The European Space Agency’s MELiSSA (Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative) program exemplifies a multi-compartment ecosystem, combining microbial bioreactors with higher-plant chambers to close material loops.

Challenges and Innovations

- Microbial Interactions: Beneficial bacteria can enhance nutrient uptake and disease resistance but require strict containment to prevent opportunistic pathogens.

- Scalability: As crew size grows, plant habitats must expand accordingly. Vertical farming techniques, such as stacked growth beds with independent light panels, increase area without drastically raising module volume.

- Genetic Engineering: Tailoring plant genomes can yield strains with accelerated growth, compact morphology, and improved stress tolerance under radiation and low-pressure conditions.

- Automation and AI: Robotic arms and computer vision systems perform planting, trimming, and harvest tasks, freeing astronauts for mission-critical activities.

Operational Strategies for Long-Duration Missions

Successful application of space agriculture hinges on mission planning, from launch to harvest. Pre-positioned seeds, deployable growth chambers, and real-time remote monitoring form the backbone of a resilient supply chain.

Seed Banking and Crop Selection

- Selecting species with high edible mass-to-biomass ratio—such as lettuce, spinach, and dwarf wheat—increases caloric efficiency.

- Maintaining a biodiversity buffer prevents monoculture collapse; including herbs and microgreens enhances crew morale and micronutrient intake.

- Long-term storage strategies, including cryogenic preservation of seeds, protect genetic viability against cosmic radiation.

Energy and Resource Budgets

Light accounts for a significant portion of power demand. Solar panels or nuclear reactors supply electricity, while heat exchangers and cooling loops manage thermal loads from LEDs and metabolic activity. Water reclamation units recover moisture from transpiration and condensation, closing the loop in H₂O cycles.

Future Perspectives and Earthly Benefits

Innovations in space agriculture drive terrestrial applications. Vertical farms, urban hydroponic installations, and drought-resistant crops benefit from technology developed for microgravity. As research progresses, integrated systems will support sustained human presence on Mars, creating a pathway to multi-planetary civilization.