Space exploration demands innovative solutions for sustaining human life beyond Earth. One of the most critical aspects of off-world habitation is the cultivation of plants in environments with minimal gravity. This article examines several **nutrient delivery** methods designed to nurture vegetation in **microgravity**, highlighting their principles, challenges, and potential for future missions.

Advanced Hydroponic Nutrient Delivery Techniques

Hydroponics has emerged as a leading approach in space agriculture, owing to its efficient use of water and precise control over mineral composition. In microgravity, however, fluid behaves unpredictably, complicating the direct immersion of roots in nutrient solutions. Engineers have thus developed systems that rely on capillary action and controlled flow to maintain consistent contact between roots and fluid.

Recirculating Flow-Through Systems

Recirculating systems pump nutrient solution through a root chamber, then filter and reuse the fluid. Benefits include:

- Reduced resource consumption via **closed-loop** circulation

- Minimized microbial contamination through continuous filtration

- Automated nutrient balancing using sensors and feedback loops

Key components of such systems consist of porous root mats, peristaltic pumps, and inline mixers that maintain homogenous distribution of **macronutrients** like nitrogen and phosphorus.

Passive Wicking and Mat Substrates

A passive approach employs wicks or foam mats that draw nutrient solution from a reservoir directly to root surfaces via capillary forces. This method eliminates moving parts, reducing mechanical failure risks. Challenges include uneven fluid distribution if wick placement is not optimized, potentially causing zones of drought or oversaturation.

Aeroponics and Fogponics in Microgravity

Aeroponics and fogponics deliver nutrients in the form of fine droplets or mist, creating an oxygen-rich environment around the root zone. Without gravity to pull droplets downward, specialized aerosol generators and airflow controls are essential to maintain droplet contact.

Ultrasonic Nebulizers and Spray Nozzles

In aeroponic modules aboard the ISS, ultrasonic transducers convert liquid into microdroplets under **ultrahigh frequency** vibrations. Alternatively, electrostatic nozzles charge droplets, guiding them to roots using electric fields. These approaches achieve:

- Enhanced **oxygenation** by suspending roots in a humid chamber

- Precise droplet size control (10–50 µm) for optimal absorption

- Adjustable misting intervals to match plant transpiration rates

Design Considerations for Zero-G Fog Delivery

To prevent droplet coalescence and fluid clumping, engineers integrate:

- Laminar airflow channels that distribute mist uniformly

- Ionizing grids to maintain droplet suspension

- Condensate recovery loops that collect excess moisture for recycling

This method faces power constraints and demands precise calibration to avoid root desiccation or root rot from prolonged wetness.

Biotic and Synthetic Approaches to Nutrient Provision

Beyond purely mechanical systems, biological and chemical innovations offer promising alternatives for **nutrient delivery** in microgravity. These strategies leverage living organisms or advanced materials to facilitate mineral uptake and maintain solution stability.

Microbial Consortia and Rhizosphere Engineering

Beneficial bacteria and fungi can colonize the root surface, enhancing nutrient availability through processes like nitrogen fixation and phosphate solubilization. In enclosed modules, inoculating plant roots with a tailored **microbial consortium** aims to:

- Accelerate nutrient cycling via enzymatic transformations

- Suppress pathogenic microbes through competitive exclusion

- Promote root development by producing growth hormones

Designing such systems requires careful monitoring of microbial population dynamics and containment protocols to avoid uncontrolled proliferation.

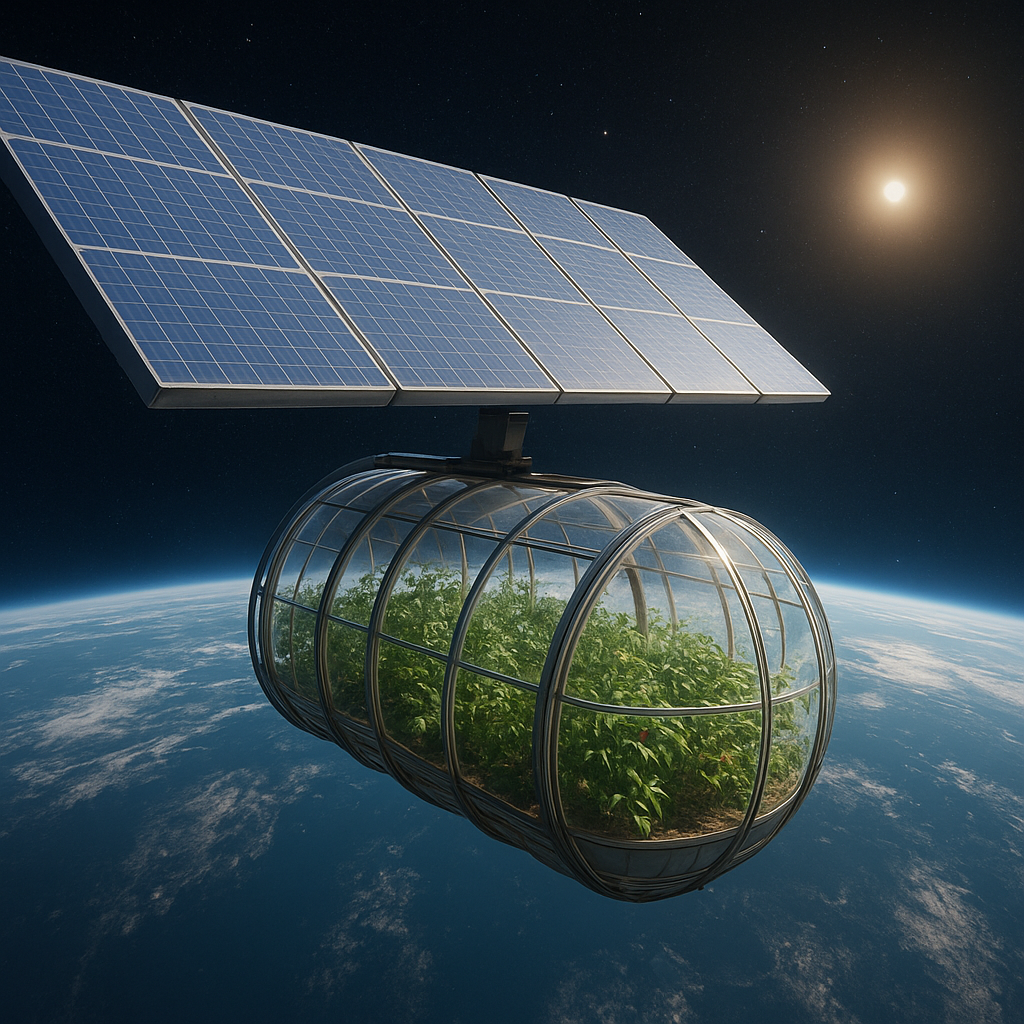

Photo-Bioreactors for On-Site Nutrient Synthesis

Photo-bioreactors harness microalgae or cyanobacteria to produce essential elements like nitrogen and carbon compounds through photosynthesis. Advantages include:

- Self-sustaining nutrient generation using crew exhaled CO₂

- Simultaneous oxygen production and carbon turnover

- Modular scaling to meet the demands of larger plant beds

Integration challenges involve maintaining stable light regimes, controlling biomass accumulation, and ensuring efficient harvesting of biochemical products for direct delivery to plant roots.

Challenges and Prospects for Long-Duration Missions

Operating nutrient delivery systems in microgravity poses unique hurdles. Engineers and biologists must address factors such as fluid behavior, energy efficiency, and system reliability to support long-duration spaceflights or extraterrestrial colonies.

Fluid Management and Leak Prevention

Unintended fluid release can damage electronic components and compromise life-support systems. Solutions include:

- Self-sealing connectors and quick-disconnect valves

- Surface coatings that repel water and reduce biofilm buildup

- Real-time leak detection sensors integrated into plumbing loops

Autonomy and Remote Monitoring

A high degree of automation is crucial for minimizing crew workload. Key features involve:

- Machine-learning algorithms that optimize nutrient dosing

- Sensor arrays measuring pH, electrical conductivity, and root respiration

- Remote telemetry systems for Earth-based specialists to fine-tune parameters

Future Directions in Space Agriculture

As humans venture toward Mars and beyond, combining multiple delivery methods may yield robust, redundant systems. Hybrid modules integrating **hydroponics**, aeroponics, and bioreactors could adapt to varying mission profiles, balancing resource constraints with plant productivity. Advances in material science—such as **nanofluidic membranes** that mimic biological ion channels—promise further enhancements in nutrient selectivity and delivery efficiency.