As humanity extends its reach beyond Earth, understanding how terrestrial life adapts to space environments becomes increasingly vital. Seed germination in microgravity offers a window into fundamental plant physiology and provides crucial insights for future extraterrestrial agriculture. By investigating how seeds sprout and develop without Earth’s gravitational cues, researchers can design robust life support systems for long-duration missions and off-world colonies.

Background on Microgravity and Plant Biology

Microgravity profoundly alters cellular processes that terrestrial plants rely on. Without a consistent gravitational vector, seeds lose the directional guidance that governs gravitropism and phototropism. On Earth, gravity helps orient roots downward and shoots upward, ensuring efficient nutrient and water acquisition. In space, these orientation cues vanish, forcing seedlings to depend on alternative signals such as light gradients, moisture distribution, and internal hormonal balances.

Key physiological processes—cell division, elongation, and differentiation—are also affected by weightlessness. Altered mechanical forces impact cytoskeletal organization, leading to changes in growth patterns. Metabolic shifts occur as microgravity influences enzymatic reactions and the transport of metabolites within plant tissues. Understanding these responses establishes a foundation for optimizing seedling health and productivity in orbital habitats and planetary bases.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

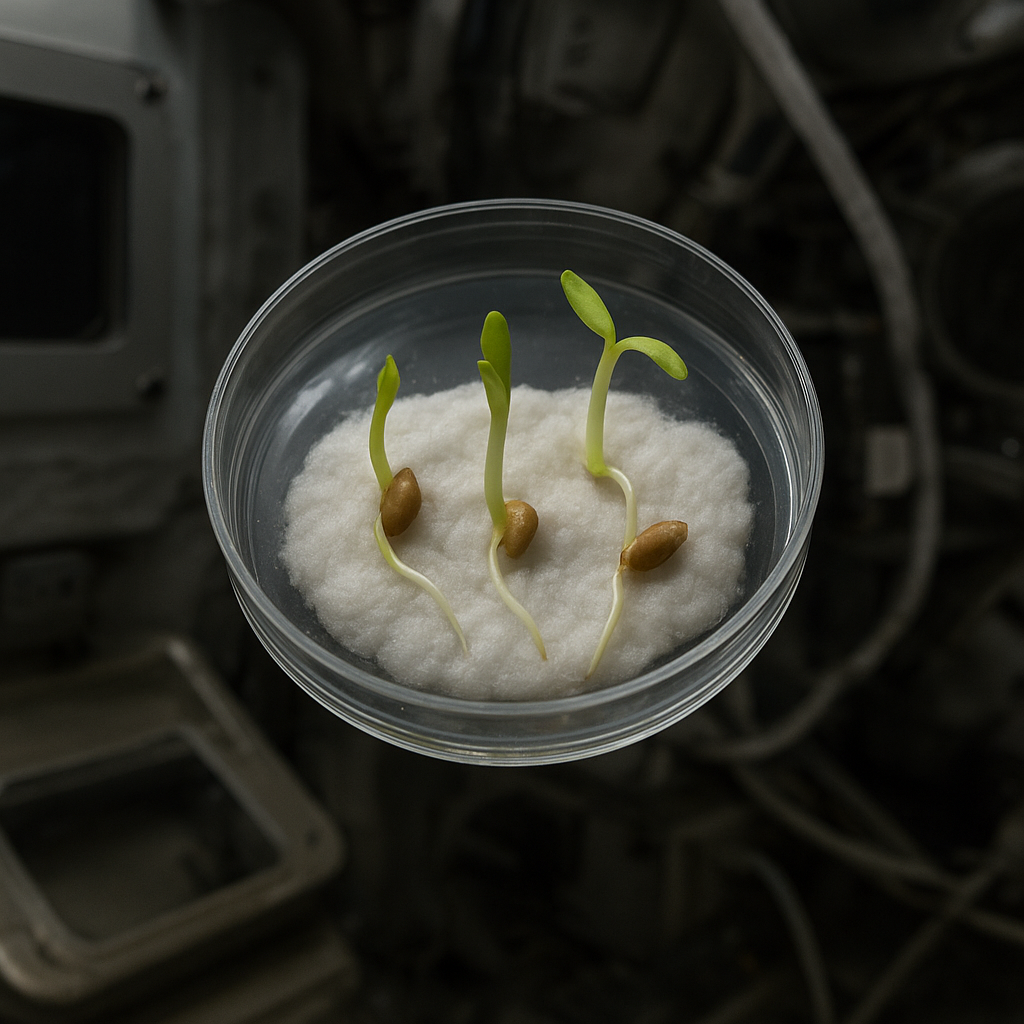

Conducting germination experiments in space demands specialized hardware and stringent protocols. Automated growth chambers aboard the International Space Station (ISS) control environmental variables such as temperature, humidity, and light cycles. Seeds are often embedded in porous substrate media—such as agar or foam—to retain moisture and provide structural support. Water delivery systems use capillary wicks or microfluidic channels to distribute hydration evenly in microgravity.

Instrumentation includes high-resolution cameras, fluorescence detectors, and environmental sensors that monitor gas composition. Telemetry streams image and sensor data back to mission control, enabling real-time adjustments. Control experiments on Earth mimic space conditions in clinostats or random positioning machines, allowing comparative analyses. Critical experimental parameters include:

- Seed type: model species like Arabidopsis and commercial crops such as wheat and lettuce

- Light spectrum: varying wavelengths to assess photomorphogenic responses

- Water imbibition protocols: timing and volume of hydration events

- Growth duration: from initial imbibition to cotyledon expansion

Meticulous documentation of hardware constraints and experimental timing ensures reproducibility across multiple flight opportunities.

Key Findings from Recent Missions

Several ISS investigations have revealed remarkable adaptations of seeds germinating in microgravity environments. Arabidopsis seedlings displayed altered root orientation, with roots spiraling or growing laterally rather than straight down. Despite these directional anomalies, the overall germination rate often matched or exceeded Earth controls, suggesting an inherent resilience in early developmental stages.

Studies on cereal grains, such as wheat, uncovered shifts in gene expression profiles linked to stress responses. Transcriptomic analyses highlighted upregulation of cell wall remodeling enzymes and oxidative stress mitigation pathways. These molecular changes likely compensate for mechanical signal disruptions, enabling robust cell elongation under weightlessness.

Lettuce cultivars experimented with on the Veggie hardware demonstrated successful leaf expansion and photosynthetic activity. Plant health assessments measured chlorophyll fluorescence and stomatal conductance, confirming functional photosystems. Such achievements pave the way for integrating fresh crops into space diets, enhancing crew nutrition and psychological well-being.

Challenges in Data Interpretation

Interpreting spaceflight plant data involves disentangling microgravity effects from secondary factors such as radiation and limited crew interaction time. Cosmic radiation can induce DNA damage and stress signaling, potentially confounding pure gravitational studies. Additionally, small sample sizes and hardware limitations restrict statistical power. Researchers mitigate these issues by employing parallel ground controls, repeated flight opportunities, and standardized protocols across different missions.

Computational models of nutrient transport and hormonal gradients provide complementary frameworks to experimental observations. By simulating auxin distribution in a gravity-free context, scientists can predict root growth trajectories and design targeted lighting regimes to steer seedlings. Integrating modeling with empirical data accelerates the optimization of space-based agriculture systems.

Implications for Space Agriculture and Future Missions

The successful germination and early growth of seeds in microgravity represent critical milestones toward sustainable off-world cultivation. Fresh produce produced in situ reduces reliance on resupply missions, cutting costs and enhancing mission autonomy. Controlled ecological life support systems (CELSS) that incorporate plant chambers can recycle water and carbon dioxide, closing resource loops. By improving crop yields and system reliability, vegetative food production contributes to crew sustainability and resilience.

On the Moon and Mars, reduced gravity environments will pose similar, albeit distinct, challenges. Lunar gravity at one-sixth Earth’s force may partially restore gravitropic cues but still lead to novel root behaviors. Martian gravity, approximately 38% of Earth’s, will require its own set of calibration experiments. Insights gained from microgravity studies inform hardware design for these destinations—optimizing irrigation, lighting geometry, and structural support to align with varying gravitational strengths.

Future Directions and Innovations

Emerging technologies promise to refine space germination protocols. Advanced sensor networks integrated with machine learning algorithms can predict and adapt to plant stress signals in real time. Bioengineered seeds with enhanced stress tolerance or synthetic biology circuits may allow precise control over developmental stages. Additive manufacturing techniques could produce bespoke growth modules tailored to specific crops and mission constraints.

International collaborations continue to expand the knowledge base, pooling data from diverse space agencies and commercial partners. As private companies develop orbital platforms and lunar landers, opportunities for large-scale agricultural demonstrations will multiply. The convergence of plant science, engineering, and space exploration heralds a new era in which life from Earth finds fertile ground beyond our planet.