Cultivating plants beyond Earth’s atmosphere demands a delicate balance of chemical and physical parameters. Among these, the regulation of pH levels and the precise management of essential nutrients are paramount to sustaining healthy growth in closed-loop agricultural modules. As space agencies and private enterprises race toward long-duration missions, understanding how to tailor these factors under unique extraterrestrial conditions becomes a cornerstone of reliable food production and crew well-being.

Understanding pH Dynamics in Space Agriculture

At its core, pH measures the concentration of hydrogen ions in a solution, determining acidity or alkalinity. In terrestrial agriculture, soil buffers moderate rapid swings, but in a microgravity environment, water behavior and ion mobility change dramatically. Without gravity-driven convection, the distribution of dissolved ions relies on diffusion, potentially creating stratified zones of varying acidity around plant roots.

Role of pH in Root Zones

Roots absorb minerals most efficiently within a narrow pH window—typically between 5.5 and 6.5 for many leafy greens. Deviations can lead to nutrient lockout, where essential elements become chemically unavailable. For instance, at a higher pH, iron precipitates as insoluble hydroxides, triggering chlorosis. Conversely, overly acidic conditions can mobilize toxic aluminum or manganese ions, impairing root cell membranes.

Impact of Microgravity on Ion Exchange

Under microgravity, solutions do not mix via convection currents. This can result in localized zones where root exudates acidify the medium, while other areas drift towards alkalinity. Engineers have responded by introducing gentle fluid circulation systems, but these require energy and add complexity. Recent experiments on the International Space Station (ISS) leverage capillary-driven wicks to maintain uniform pH profiles, harnessing surface tension to distribute nutrient solutions evenly around plant roots.

Optimizing Nutrient Delivery Systems

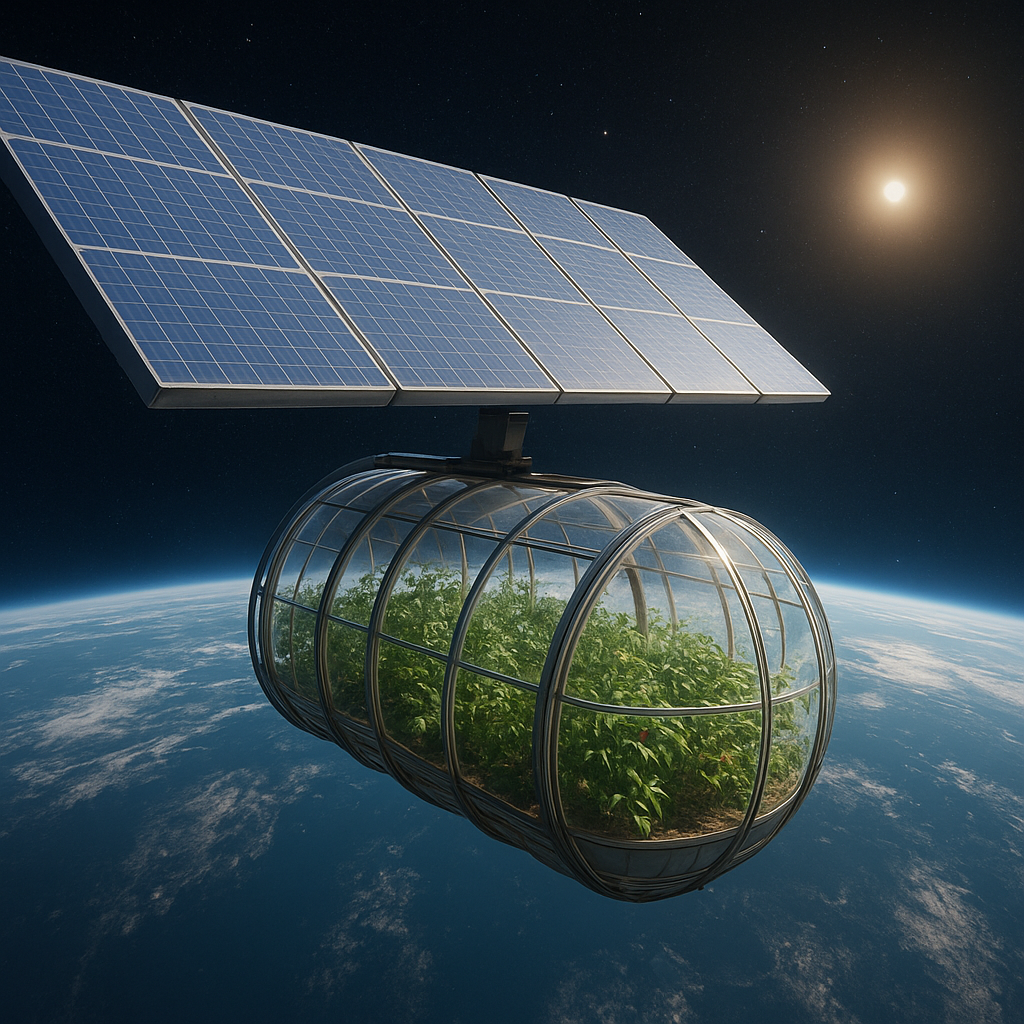

Delivering the full complement of elemental nutrients—nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and trace metals—poses logistical challenges in space. Conventional soil is heavy and inconsistent, leading to hydroponic, substrate-based, and aeroponics systems becoming the frontrunners for extraterrestrial farming.

Hydroponics: Water-Based Precision

- Uses inert media or no media at all, relying on circulating nutrient solutions.

- Enables tight control of nutrient concentration via frequent monitoring.

- Prone to biofilm buildup if roots overgrow and block fluid channels.

Substrate Culture: Granular Support

- Employs materials like zeolite or lava rock to anchor roots.

- Buffers rapid changes in pH by adsorbing cations and releasing them slowly.

- Requires periodic flushing to prevent salt accumulation in pore spaces.

Aeroponics: Mist-Driven Efficiency

- Roots hang in a misting chamber, receiving fine droplets of nutrient solution.

- Maximizes oxygen availability, boosting photosynthesis rates.

- Demands precise droplet size control; clogging of nozzles can starve roots instantly.

Integration of pH and Nutrient Control Techniques

Combining accurate pH regulation with dynamic nutrient delivery systems necessitates advanced monitoring and feedback loops. Emerging technologies focus on real-time sensing, automated adjustments, and bioregenerative cycles that recycle waste into plant feedstock.

Real-Time Monitoring with Smart Sensors

Miniaturized probes now measure pH, electrical conductivity, and dissolved oxygen simultaneously. These sensors embed within root zones or float in reservoirs, transmitting data wirelessly to a central controller. By analyzing trends, the system can predict drift and initiate corrective actions—adding acid or base or adjusting nutrient concentrate—to maintain ideal conditions.

Automation and Feedback Loops

Integrated controllers manage pumps and valves to dose reagents on demand. For example, if pH drifts above 6.5, a small volume of dilute acid is injected until the sensor reads back within tolerance. Similarly, if potassium levels dip below a threshold, a premixed solution rich in that macronutrient is added. These loops reduce crew time and error, crucial for missions with limited human oversight.

Bioregenerative Approaches

Closed systems aim to recycle inedible biomass and human waste into nutrient stocks. Through microbial reactors, organic matter undergoes decomposition, releasing ammonium and phosphate. Subsequent nitrification converts ammonium to nitrate, the preferred nitrogen form for most crops. Maintaining correct pH in these reactors is vital: nitrifying bacteria operate best near pH 7.0, whereas denitrifiers prefer slightly acidic conditions. Balancing these processes ensures a steady supply of nutrients without frequent resupply from Earth.

Future Directions in Space Crop Chemistry

As missions extend toward Mars and beyond, agricultural modules will become increasingly autonomous. Development trends include:

- Advanced chelators to keep trace metals soluble across wide pH ranges.

- Smart membranes that selectively permit nutrient ions while excluding pathogens.

- In situ resource utilization, extracting minerals from regolith to supplement nutrient solutions.

- Use of aeroponics to maximize yield per unit volume, critical for confined habitats.

Ultimately, mastering the interplay of pH and nutrient balance under microgravity or partial gravity environments will unlock sustainable food production. By integrating robust monitoring, adaptive delivery systems, and biological recycling, future crews will rely on verdant gardens to nourish body and mind across the solar system.